Tintype, also melainotype and ferrotype, is a photograph made by creating a direct positive on a sheet of metal, usually iron or steel that is blackened by painting, laquering or enamelling and is used as a support for a collodion photographic emulsion.

Photographers usually worked outside at fairs, carnivals etc. and as the support of the tintype (there is no actual tin used) is resilient and does not need drying, instant photographs can be produced only a few minutes after taking the photograph.

An ambrotype uses the same process and methods on a sheet of glass that is mounted in a case with a black backing so the underexposed negative image appears as a positive. Tintypes did not need mounting in a case and were not as delicate as photographs that use glass for the support.

The process was identical to the wet plate process, where collodion is employed to produce a photographic emulsion where silver halide crystals (silver bromide, silver chloride and silver iodide) are suspended in the collodion, and are chemically reduced to crystals of metallic silver that vary in density according to the original light values of the original image.

When a photographic negative image on film or plate is very underexposed, it appears as a positive when viewed against a dark background. This is the basis of the process: a very underexposed image is produced on a collodion photographic emulsion on a dark metal backing; thus viewed the image appears as a positive. The fact that an underexposed image is required means that the effective film speed is increased and shorter exposures can be used, which is a great advantage in portraiture.

The process was first described by Adolphe-Alexandre Martin in France in 1853, and patented in the United States on February 19, 1856 by Hamilton Smith, professor at Kenyon College, in Ohio William Kloen also patented the process in the United Kingdom in the same year. It was first called melainotype, and then ferrotype (by a rival manufacturer of the iron plates used); finally came the name tintype. All three names describe both the process and the resulting photograph.[1]

The ambrotype was the first wet-plate collodion process, invented by Frederick Scott Archer in 1851 and introduced in the United States by James Ambrose Cutting in 1854.

While the ambrotype remained very popular in the rest of the world, the tintype process had superseded the ambrotype in the United States by the end of the Civil War. It became the most common photographic process until the introduction of modern, gelatin-based processes and the invention of the reloadable amateur camera by the Kodak company. Ferrotypes had waned in popularity by the end of the 19th century, although a few makers were still around as late as the 1950s and the images are still made as novelties at some European carnivals.

The tintype was a minor improvement to the ambrotype, replacing the glass plate of the original process with a thin piece of black-enameled, or japanned, iron (hence ferro). The new materials reduced costs considerably; and the image, in gelatin-silver emulsion on the varnished surface, has proven to be very durable. Like that of the ambrotype, the tintype's image is technically negative; but, because of the black background, it appears as a positive. Since the tintype 'film' was the same as the final print, most tintype images appear reversed (left to right) from reality. Some cameras were fitted with mirrors or a 45-degree prism to reverse (and thus correct) the image, while some photographers would photograph the reversed tintype to produce a properly oriented image.

Tintypes are simple and fast to prepare, compared to other early photographic techniques. A photographer could prepare, expose, develop, and varnish a tintype plate in a few minutes, quickly having it ready for a customer. Earlier tintypes were often cased, as were daguerreotypes and ambrotypes; but uncased images in paper sleeves and for albums were popular from the beginning.

Ferrotyping is a finishing treatment applied to glossy photo paper to bring out its reflective properties. Newly developed, still-wet photographic prints and enlargements that have been made on glossy paper are Squeegeed onto a polished metal plate called a ferrotyping plate. When these are later peeled off the plate, they retain a highly reflective gloss.

skip to main |

skip to sidebar

I have been thinking of why I love photography, it comes down to something I have labeled "The Three Joys"

1) Creativity

The first joy is simply creating the work. Everything about the making of photographs I love. The initial ideas, the writing on the blog, the preparation of equipment, the research into my subjects, figuring out what I want to communicate. The camera tech stuff like composition, lens selection, cameras, figuring exposure, taking the shot etc. The post darkroom work where you swim with your prints bringing them slowly to life, creating something powerful and beautiful. I love it all.

It is so powerful a thing, you have a idea in your mind, there is nothing else, then YOU make it, you create it, it's fricking awesome stuff.

2) The People

The second joy is that photography has allowed me a way into so many peoples lives, so many different worlds. I get to meet people of all types, speak to them, eat with them, cry and laugh with them. For a while I get to live their existence to be them if you will.

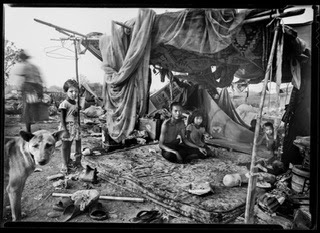

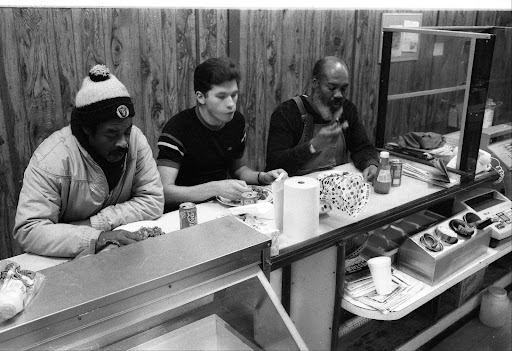

I get to be a child in a slum in Bangkok or a drug addict in a ghetto in Oakland. I get to be a ladyboy sex worker in Pattaya or a man dying of cancer in Canada. Of course I am not really those people but I get a true flavor for those worlds, those experiences, the good and the bad, the ugly and the beautiful, the joy and the sadness.

With photography I get a chance to live outside of the same same everyday meat and potato lives many of my friends and family live. Because I use a camera and make pictures all the doors to a wonderful life experience are open to me, photography is a window into everything!

3) The Photograph

The third joy is about the feeling you get when you accomplish your goals, when you see your final print in the developer, fix or hanging in a gallery. There is a special emotion there, a true satisfied happiness, something so uniquely rewarding. In the darkroom sometimes when I see the finished photo for the first time as it lays in the fixer tray I will let out hoops of joy. I will scream and shout. It is quite a spectacle! It's just the sheer high of that moment bursting out, the YES moment. When the photo is right and you see it for the first time it's the best feeling in the world, better than anything I have ever felt, the high of highs!!

"Ain't Photography Grand!"

Contact Gerry Yaum

contact@gerryyaum.net

"Black & White" Photography Magazine, Issue #160

Search This Blog

Me, W. Eugene Smith, Sebastiao Salgado, Lewis Hine and Walker Evans! :) NOT!!!

LUNCHBOX Radio Interview FOR UNB EXHIBITIONS

MONEY EARNED TO HELP THE PEOPLE IN THE PICTURES

Money that will be used to directly help the people in our two photography projects, THE FAMILIES OF THE DUM and THE PEOPLE WHO LIVE UNDER THE FREEWAY $6334.67 ($6000 earned when 6 prints were added to the UNB permanent collection).

GOFUNDME, FAMILES/FREEWAY

Trying to raise $2000 to help the people under the freeway, and the families of the dump. TOTAL RAISED SO FAR = $325 —->$314.67 (after GOFUNDME fees).

UNIVERSITY OF NEW BRUNSWICK EXHIBITIONS VIDEO

Analog Forever Magazine

Vernon Morning Star Newspaper Story

2022 "Families of the Dump"/The People Who Live Under The Freeway Donation Buys

Total donation money spent for the 2022 trip to the Mae Sot dump (THE FAMILIES OF THE DUMP), Bangkok's Klong Toey Slum (THE PEOPLE WHO LIVE UNDER THE FREEWAY). Money spent on "The Families of the Dump" = $571.17 CAD (14982 Thai Baht) Money spent on "The People Who Live Under The Freeway = $144 CAD (3849 Thai Baht) General cases where money was spent to help others in need $15 CAD (401baht)

(Thai Currency) or

CAD

"Families of the Dump" Donation Total

$4420.02 CAD

GERRY YAUM: YouTube Video PHOTOGRAPHY CHANNEL

THE GOAL

To create photographs that speak to the universality, the commonality and the shared humanity of all peoples, regardless of country, race, culture or language.

TRANSLATE YAUM'S PHOTO DIARY INTO YOUR LANGUAGE

Quote: Robert F. Kennedy

“The purpose of life is to contribute in some way to making things better.”

Quote: Nelson Mandela

"As long as poverty, injustice and gross inequality persist in our world, none of us can truly rest."

Quote: Weegee (Authur Fellig)

"Be original and develop your own style, but don't forget above anything and everything else...be human...think...feel. When you find yourself beginning to feel a bond between yourself and the people you photograph, when you laugh and cry with their laughter and tears, you will know your on the right track....Good luck."

Blog Archive

-

▼

2009

(254)

-

▼

February

(36)

- Final Scans Of The Day (before my eyes fall out!)

- More More More More Lost Negs

- More More More Lost Negs

- More More Lost Negs

- More Lost Neg Scans

- Today's Lost Negs

- Ring Flash

- Lost Negs Rediscovered

- Working With Scanner

- Quote: Norman Seider (Cinematographer)

- Interview With An Artist

- Quote: Anais Nin

- Tintype: Civil War Era Young Freckled Girl

- Tintype: Young Woman Gypsy

- Quote: Brassai

- Daguerreotypes: Three People

- Abrotype: Mother and Daughter

- Photo Stories

- Quote: Henry David Thoreau

- Tintype: Wikipedia

- Tintype: Fierce Looking Man

- Daguerreotype: Old Lady in Bonnet

- Negative Scanner

- Got To Use Up That Darn Film!

- Gerry the Collector

- Victorine Meurent

- Olympia Influence

- Mr. Manet

- Cross Dresser Meeting

- Collected

- Understanding Transgender Issues

- It All Comes Down to Making Photos

- Things To Do

- More Sex Worker Images

- Mary Ellen Mark Photograph

- Nit 49 Freelance Sex Worker

-

▼

February

(36)

Total Pageviews

The Three Joys Of Photography

The Three Joys

1) Creativity

The first joy is simply creating the work. Everything about the making of photographs I love. The initial ideas, the writing on the blog, the preparation of equipment, the research into my subjects, figuring out what I want to communicate. The camera tech stuff like composition, lens selection, cameras, figuring exposure, taking the shot etc. The post darkroom work where you swim with your prints bringing them slowly to life, creating something powerful and beautiful. I love it all.

It is so powerful a thing, you have a idea in your mind, there is nothing else, then YOU make it, you create it, it's fricking awesome stuff.

2) The People

The second joy is that photography has allowed me a way into so many peoples lives, so many different worlds. I get to meet people of all types, speak to them, eat with them, cry and laugh with them. For a while I get to live their existence to be them if you will.

I get to be a child in a slum in Bangkok or a drug addict in a ghetto in Oakland. I get to be a ladyboy sex worker in Pattaya or a man dying of cancer in Canada. Of course I am not really those people but I get a true flavor for those worlds, those experiences, the good and the bad, the ugly and the beautiful, the joy and the sadness.

With photography I get a chance to live outside of the same same everyday meat and potato lives many of my friends and family live. Because I use a camera and make pictures all the doors to a wonderful life experience are open to me, photography is a window into everything!

3) The Photograph

The third joy is about the feeling you get when you accomplish your goals, when you see your final print in the developer, fix or hanging in a gallery. There is a special emotion there, a true satisfied happiness, something so uniquely rewarding. In the darkroom sometimes when I see the finished photo for the first time as it lays in the fixer tray I will let out hoops of joy. I will scream and shout. It is quite a spectacle! It's just the sheer high of that moment bursting out, the YES moment. When the photo is right and you see it for the first time it's the best feeling in the world, better than anything I have ever felt, the high of highs!!

"Ain't Photography Grand!"

Contact Gerry

- Gerry Yaum

- Edmonton, Alberta, Canada

- Email Gerry: gerryyaum@gmail.com

"Can a photograph stop a war? Can it save a life? Can it lead to understanding, inspire someone to help, provide comfort and open the door to compassion?

Hope that it can.

Pray that it can."

Hope that it can.

Pray that it can."