Asked by his biographer whether, at 75, if he still had "the fire" in him, Mr. Stapleton reflected, "Sure, I still get passionate about causes, about inequity and inequality, about what's wrong with our society, with the environment and with the economic system ... Look, you have to have anger, passion, indignation, love, tenderness - the whole gamut of human emotion - if you're going to be a real artist. Injustice is always with us, and one of the jobs of responsible artists is to respond to it. Art becomes an essential voice in all the chaos of our times: A tool for bearing witness, and a weapon for effecting change."

He never made a living at art, he admitted, "but I lived through it."

BILL STAPLETON, 92: ARTIST

He used his brush as a weapon to empower the powerless

Once a sincere and ardent Communist, he spent more than 60 years depicting strikes, refugee camps, political rallies, native reserves and the lives of ordinary working people

RON CSILLAG

Special to The Globe and Mail

February 16, 2008

TORONTO -- Bill Stapleton was more than just another artist with a social conscience. His documentary art prodded, pushed, shamed, confounded and made people think (and sometimes squirm). He knew that not many people wanted to hang socially relevant art like his over their living-room sofas. It was just as well.

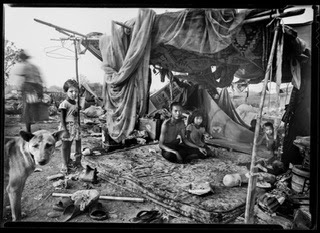

No bucolic landscapes, postcard portraits or pictures of fruit for him, but fulminations against inequality, oppression, poverty and the misery of society's dispossessed. These were powerful reminders of humanity's shortcomings, but also depictions of the inner strength and dignity of people accustomed to hardship.

In the words of his biographer, Mr. Stapleton held "strong, unabashedly partisan empathy" with the compositions the artist called "Human-scapes."

Largely unsung, though he was once dubbed "the People's Artist," Mr. Stapleton was a committed socialist, activist and a sensitive, persuasive man "who celebrated the dignity and independence of the human spirit without irony but not without humour," wrote C.H. (Marty) Gervais in People In Struggle: The Life and Art of Bill Stapleton (Penumbra Press; 1992).

Print Edition - Section Front

Enlarge Image

Working in a variety of media - pen-and-ink, charcoal, watercolour, ink wash, oils and acrylics - Mr. Stapleton spent more than 60 years depicting strikes and picket lines where workers squared off against police and company goons, refugee camps where he heard tales of torture, women's rallies and the lives of ordinary working people, and native reservations where he faithfully recorded disgusting poverty.

"Sketching is honest and immediate," he'd say. "You can't go back and pretty it up."

His artistic activism wasn't limited to Canada. He journeyed to Mexico and Central America to document injustice and despair with nothing more than brushstrokes.

"People have been neglected," Mr. Stapleton explained on his 90th birthday, "and that's why I've concentrated on them. Social art doesn't play enough of a role in art." He saw his role as almost journalistic, a visual Upton Sinclair whose solidarity with his subjects only hardened. Mr. Stapleton was committed to using his craft "as a tool and weapon for the benefit of the powerless and the denunciation of the powerful," Mr. Gervais found.

Collections of Mr. Stapleton's work are housed in the National Archives of Canada and, ironically for a man who worked so hard toward peace, in the Canadian War Museum. In 2006, he donated more than 1,500 canvases and sketches to the Cabbagetown/Regent Park Community Museum in Toronto.

Born and raised in middle-class comfort in conservative small-town Ontario, his father was a salesman. A 1933 strike at a local food plant that was violently suppressed left a deep mark on him. "The father of a friend of his was beaten in that strike," said his daughter, Lynn Taylor. "That left a very raw impression. It had a lot to do with influencing his politics later in life."

He planned to become an engineer and, to that end, accepted a job surveying the Trans-Canada Highway in White River, Ont., north of Lake Superior. The Depression was on and he was grateful for the work. His older brother, Bruce, an illustrator well known for his war-bonds and Red Cross posters, sent him some paints, and Mr. Stapleton sketched the scenery and his fellow workers - 12 to a tarpaper bunkhouse. With little else to do after long, gruelling days, he honed his talents, sending pieces to his brother, who returned them with notations suggesting improvements.

He toiled in the north for 18 months and, with $800 in savings, headed to New York City where he studied art at the U.S. National Academy of Design, and where the apolitical 21-year-old first encountered radical politics. His roommates in a teeming tenement near Central Park were leftists, and the Big Apple was a magnet for Marxists. Finding and sketching hobos and street urchins a stone's throw from the gleaming towers of Wall Street helped seal his political views.

But New York was as competitive as people had warned. After two years, he failed to find work as an illustrator and came home. In Toronto, he worked as a printing salesman, which allowed him to take evening classes at the Ontario College of Art.

In 1941, Mr. Stapleton was emboldened to join the Communist Party of Canada after Ottawa banned it. This was no act of petulance but a sincere belief that the party could better achieve the dreams of social justice than other leftist groups. (He would quit the party in the early 1950s, dismayed by Stalin's treatment of artists in the Soviet Union.)

Later in 1941, when the Soviet Union entered the Second World War, he signed up for service in the Royal Canadian Air Force and became a pilot. It was around this time he first achieved recognition. A work of his titled Canadian Airman was included in a travelling Canadian military exhibit.

Shipped to several bases in England, he ended up with the 418th RCAF Squadron in North Yorkshire and trained on Wellington and Lancaster bombers. But the war ended before he could fly any missions.

Meantime, he'd sketched.

"It got so I was annoyed if we had to fly because it cut into my art time," he would recall to his biographer. "I usually rode a bicycle, with a small canvas bag I could sling over my shoulder, and I'd pedal off to sketch. Fortunately for me, when the fog set in - and this was quite often, English weather being what it is - we'd be grounded for two or three days. It was a great opportunity, and not having to make art to make money was like being subsidized."

At war's end, he chose to stay in London to study at the famed Slade School of Art. Though his own war art portfolio grew, an appointment as an official war artist eluded him, and he returned to Canada in time to document two seminal strikes, one by Stelco workers in Hamilton in 1946, and the other by the Canadian Seaman's Union in 1949 on the waterfronts of Welland, Toronto and Montreal.

That same year, he married Margaret (Mickey) Rylance. He'd met her at an art show, and later explained that he fell for her despite the fact she believed in God.

With a family to support, he started his own advertising agency and bought a cottage and a split-level house in Toronto. The middle-class life was maybe not what communists aspired to, but "with a wife and three daughters and a couple of mortgages, I had to have a job - so I went into the advertising business. It was a living." There was a line he once heard about working in advertising and loved to quote: "I never told my mother I was in advertising. She thought I played piano in a brothel."

In 1974, he visited Russia on a cultural exchange. Describing it as the trip that had the greatest impact on him, Mr. Stapleton reconciled conflicted feelings. "They led the world in science and were the first to the moon. Freedom of the sexes, women were ship captains and factory heads. Socialism led the world then, but was betrayed from within and without. I still believe in revolution."

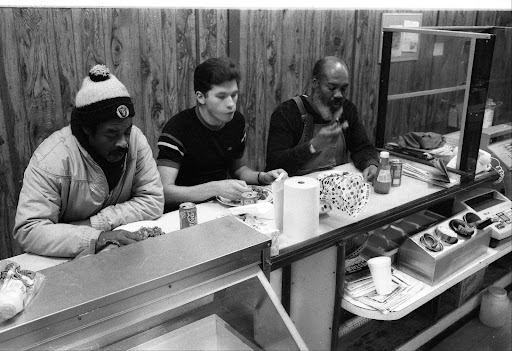

He divorced his wife after 23 years of marriage - there were no hard feelings and the two stayed friends - and moved to Toronto's Cabbagetown neighbourhood ("it was here I joined the human race") where he began depicting ordinary people doing ordinary things. For about a decade, he was resident artist at three Toronto landmarks: The Hotel Winchester, the Paramount Tavern, and the Trojan Horse Coffee House. He'd sit for hours, sketching and painting exiled Chilean musicians, leftist activists, and the regulars.

"I liked pubs like the Paramount," he recalled. "It attracted a mostly black clientele. The guys were cocky, exuberant and graceful; they just had this way of moving and expressing themselves. And their music - wow! The mixed clientele provided a real slice of life - fights, shootings, stabbings and four police vans on a Saturday night."

As for his style, it had a relaxed structure but his lines were "direct and bold, drawn with rock-steady hand and a sharp eye," noted Carol Moore-Ede, Mr. Stapleton's friend and curator. "He painted in startlingly vibrant colours and bold strokes, as forthright in his technique as he was in his social convictions."

One reviewer lauded his oeuvre as being in the tradition of Edgar Degas and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec.

His pace quickened in his sixties and seventies. He journeyed to Nicaragua in 1982 to sketch the suffering and despair caused by the country's political upheaval. In 1984, he went to Mexico to document the scores of Guatemalan refugees flooding the border in a struggle for safety and food. The following year, he was part of a delegation that travelled to Spain to seek recognition for the 1,239 Canadians of the Mackenzie-Papineau Battalion (the "Mac-Paps") who fought the fascists in the Spanish Civil War. And in 1989, he joined the Innu of Sheshatshit, Labrador, to protest low-level test flights of NATO fighter jets and bombers over traditional native hunting grounds. An exhibit was mounted in Toronto.

He belonged to Veterans Against Nuclear Arms, and in the early 1980s, helped mobilize artists in a national disarmament movement, Arts for Peace, chaired by novelist Margaret Laurence and numbering the likes of Pierre Berton, Norman Jewison, Margaret Atwood and Karen Kain.

In his later years, he volunteered for ArtHeart, a community-based effort that provides free access to studio space, instruction, and art supplies. He'd give away quick sketches to children.

Just last December, he received the Ontario Federation of Labour's first Lifetime Cultural Achievement Award. His age prevented his attendance but he received a standing ovation nonetheless.

Asked by his biographer whether, at 75, he still had "the fire" in him, Mr. Stapleton reflected, "Sure, I still get passionate about causes, about inequity and inequality, about what's wrong with our society, with the environment and with the economic system ... Look, you have to have anger, passion, indignation, love, tenderness - the whole gamut of human emotion - if you're going to be a real artist. Injustice is always with us, and one of the jobs of responsible artists is to respond to it. Art becomes an essential voice in all the chaos of our times: A tool for bearing witness, and a weapon for effecting change."

He never made a living at art, he admitted, "but I lived through it."

BILL STAPLETON

William Johnson Stapleton was born in Stratford, Ont. on Jan. 24, 1916. He died in Bracebridge, Ont. on Feb. 5, 2008. He was 92. He is survived by daughters Lynn Taylor, Judith Stapleton and Sharon Sherman. He also leaves his former wife, Mickey, and five grandchildren.

An exhibition of Mr. Stapleton's selected works, is on display at Riverdale Farm, 201 Winchester St., Toronto, Saturdays from 11 a.m. to 3 p.m. until March 23.